You still have another five weeks to enjoy the exhibition as it is, and make sure you don’t miss the final nine days when we will have added our brand new Aardman Expression Lab. Keep an eye on our website for more about that soon, but back to the blog post…

I have been involved with this exhibition for about a year. It was my job to try to work out what story we would tell, and how we could tell it. For every exhibition, these decisions are influenced by many things: the overall mission of the museum, the specific audience identified for the exhibition, and of course what items from our collection are relevant to the theme and available for use.

Initially, we had an embarrassment of riches, everything with a face was a potential inclusion—the possibilities seemed endless… and, believe it or not, that’s not really a good thing!

So followed a long and at times arduous period of focusing our messages and ideas down to something clear, easy to communicate and fun. We ended up with this:

The exhibition aims to explore the scientific and cultural ways in which we record, perceive and respond to faces.

This new focus made our object selection very clear, and as always, left many of our original thoughts and ideas outside in the cold (or on the ideas list for the future…) At this point, we dismissed the inclusion of any in-depth exploration of the portraits and self-portraits in our collection—that would be a whole different exhibition. Early research into the portraits was, however, the part of the exhibition development I enjoyed the most, so here is a small selection of my highlights.

Photographers have always been very interested in capturing faces. Often it’s their own face they like the most.

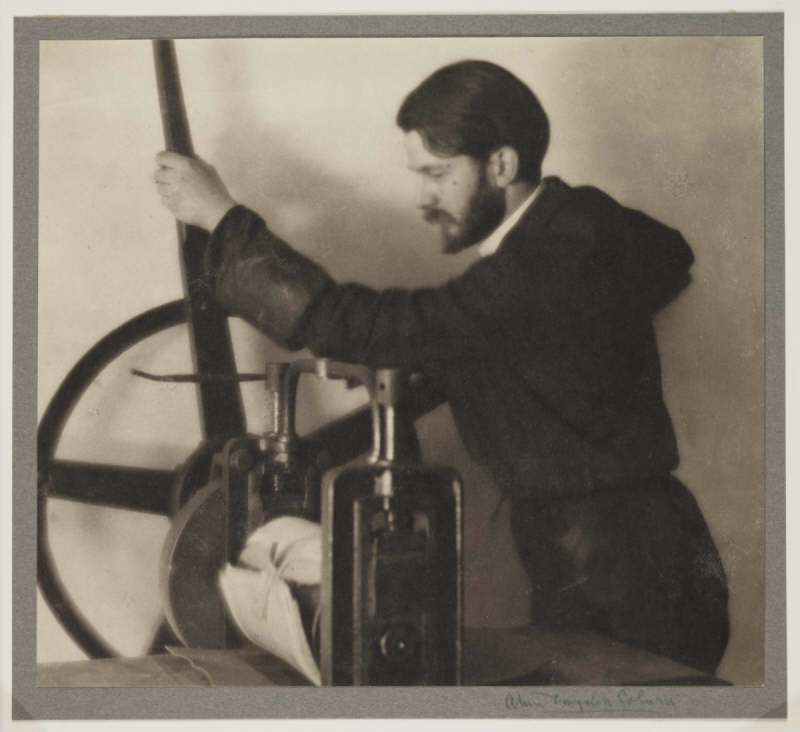

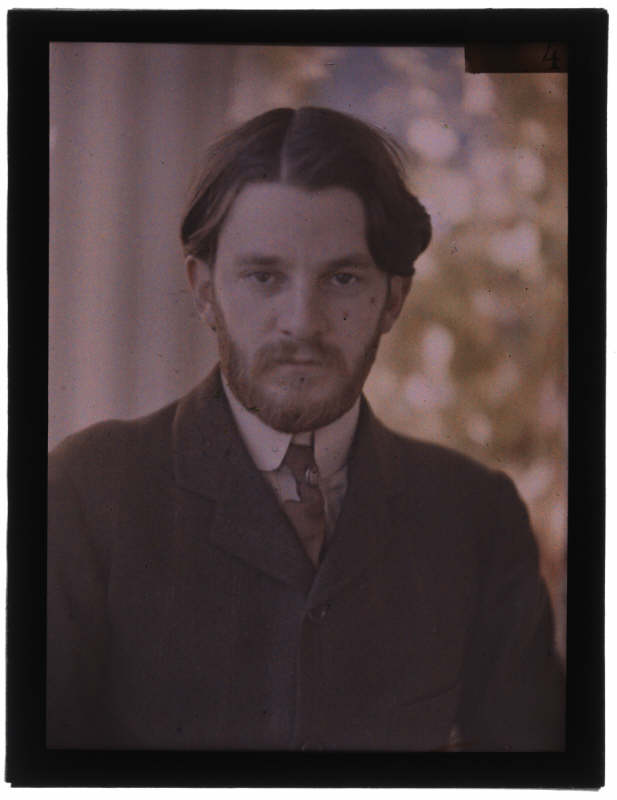

Alvin Langdon Coburn was a serial selfie taker. The two images below were taken five years apart. They show the photographer experimenting with different styles and processes. The Platinum print from 1905 shows Coburn as the photographer at work; the brooding autochrome from 1910 looks like it could have been taken very recently. Dressed in what looks like his ‘Sunday best’, he stares straight into the camera—do you get an idea of what this man was like? Does his personality show through?

It is very clear from this self-portrait that Helen Messinger Murdoch was proud of her roots:

Choosing to present herself in front of the American flag, her favoured photographic technique, the autochrome, was perfect to highlight the red, white and blue of the symbol of her home. Messinger Murdoch was a great traveller and captured portraits all around the world. See this blog post for more of her amazing photographs.

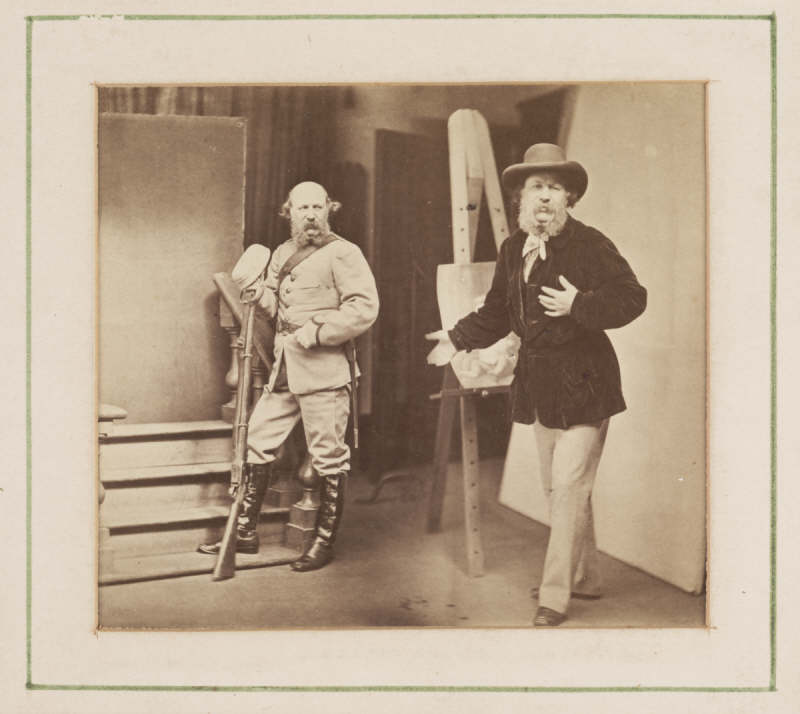

Oscar Rejlander also liked to photograph his own face. In the composite image below, we see the two sides of his life: Rejlander the artist and Rejlander the volunteer soldier. If you could take two contrasting self-portraits to illustrate your life, what would they show?

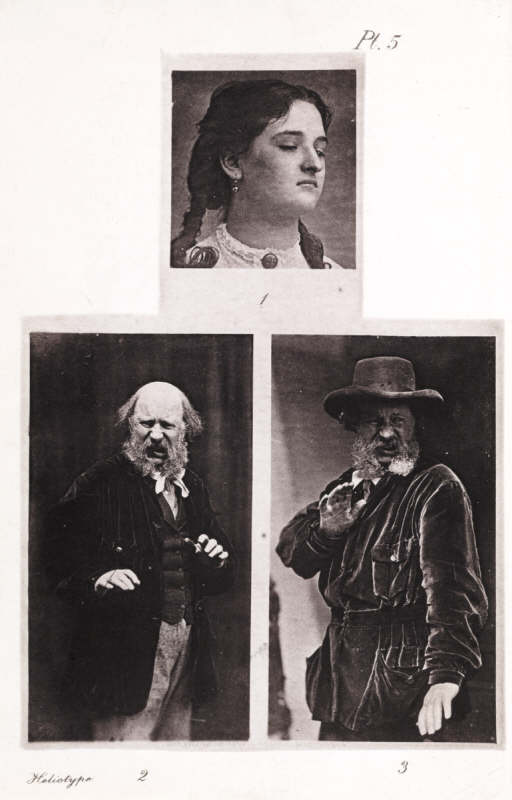

And if you thought that was weird, here is Rejlander again, this time posing for a book—Charles Darwin’s The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, 1872. In case you were confused, he is ‘doing’ contempt.

One more, and possibly my favourite.

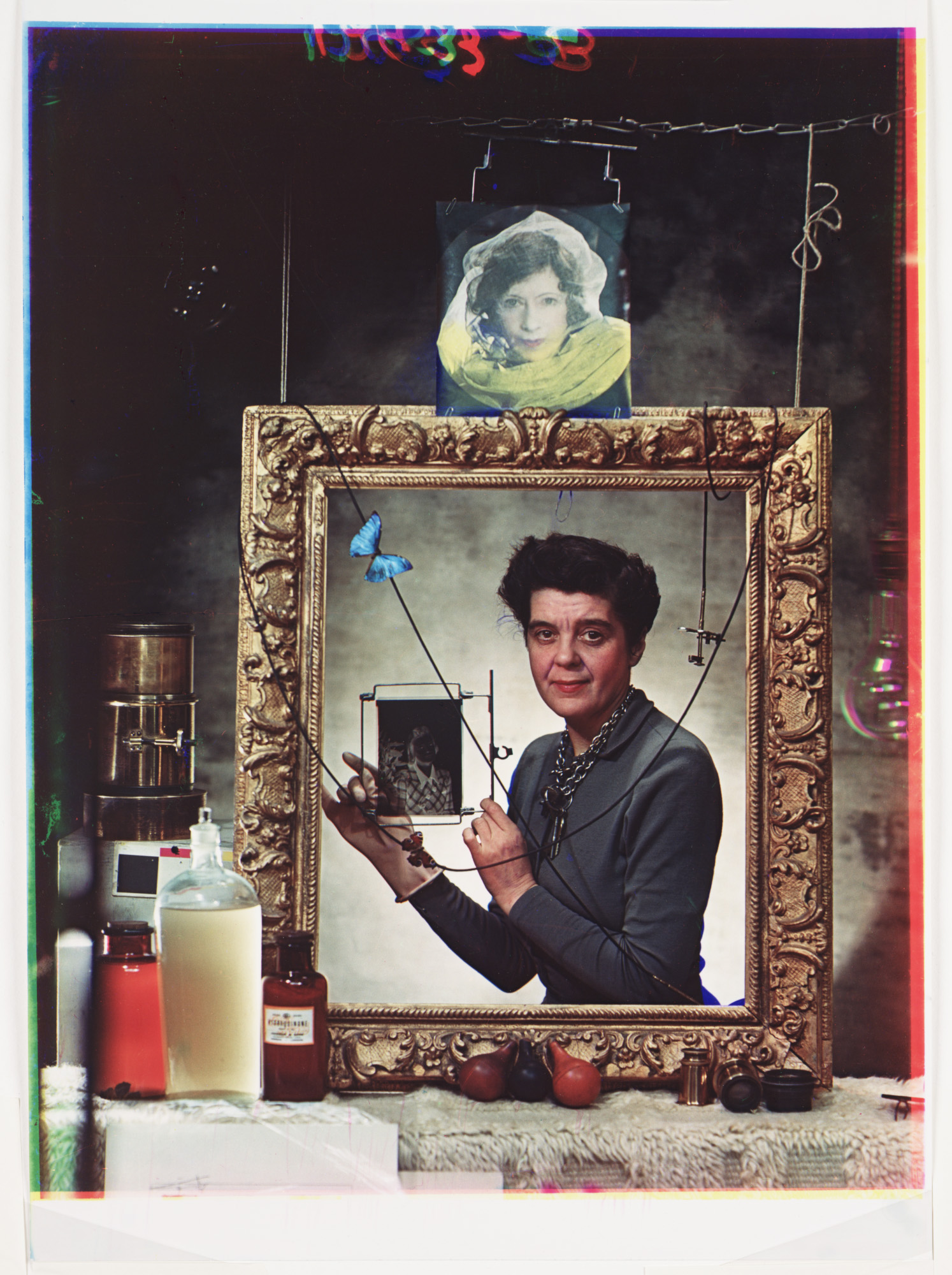

Madame Yevonde is a photographer hero of mine. I mean, just look at the image below. The colours, the symbolism, it’s such an amazing portrait. We have several self-portraits by Madame Yevonde in our collection. In this one, she chooses to depict her working self, surrounded by the tools of her trade, even including one of her famous portraits within the self-portrait. She uses butterflies and camera shutter release balls arranged at the bottom of the frame like fruit. This is a nod to the traditions of still life painting, saying very clearly, I am a photographer and I am an artist.

In Your Face is open until 30 October 2016. There are plenty of opportunities to take selfies or even have a professional portrait taken. Come along and bring your friends!