As someone without a background in photography, film, television, or media, I often find myself mystified by the objects I deal with on a daily basis. However, I regularly come across material that no amount of expertise can prepare you for. In this series I’m going to highlight some of the weird and wonderful objects I come into contact with down here in the museum’s collection stores.

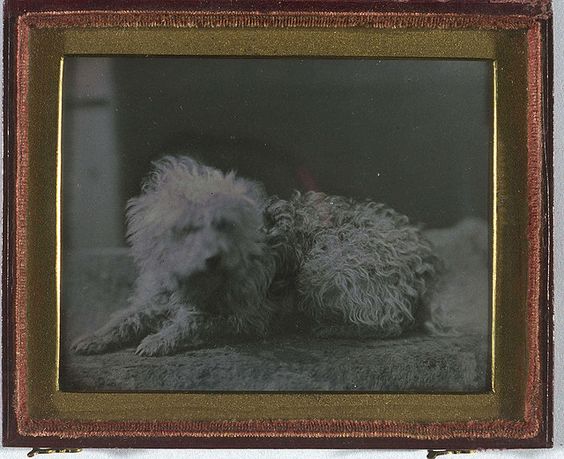

‘Dog-erreotype’

© Science Museum Group collection

I say this about every entry in this series, but I think this is one of my favourite objects in our collections here. It’s a piece I can’t resist showing to tour groups, and it never fails to get at least one person saying ‘aww!’ And who can blame them? The real wow factor for this piece, though, is that it is one of the earliest photographs of a pet in the world!

It’s certainly not unusual for someone to take a picture of a beloved pet. With the ease of digital photography pet lovers often seem to have an unlimited number of images of their animal companions. But this practice most certainly predates digital. Growing up we had no small number of prints of our dog, Tess, in my home (perhaps even more than of me now that I think back). We love our companions of varied species, and we want to display that just as much as we would for anyone else we care about (perhaps even more so!)

The image of the dog was made through the daguerreotype process, which was the earliest photographic process that was announced to the public, back in 1839. It uses photo-sensitive chemicals to create an image on the surface of a metal plate. In its first years, the exposure times were so long (a matter of hours) that it was only used for photographs of landscapes or other subjects that tended not to fidget.

© Science Museum Group collection

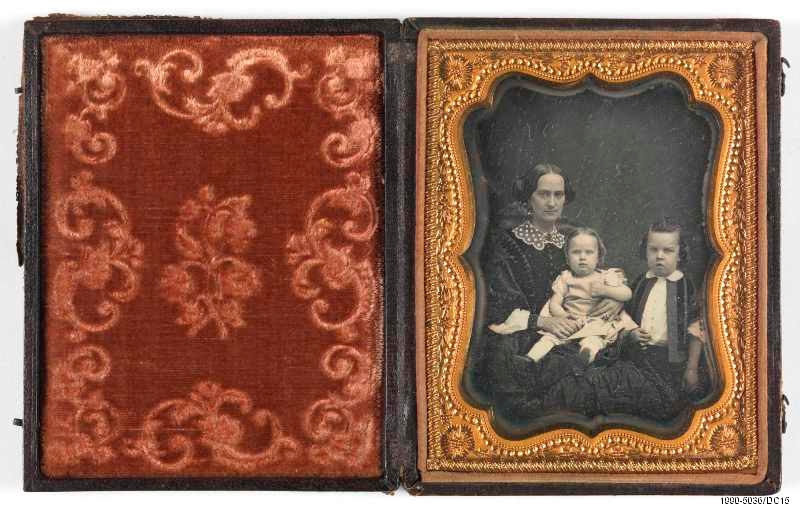

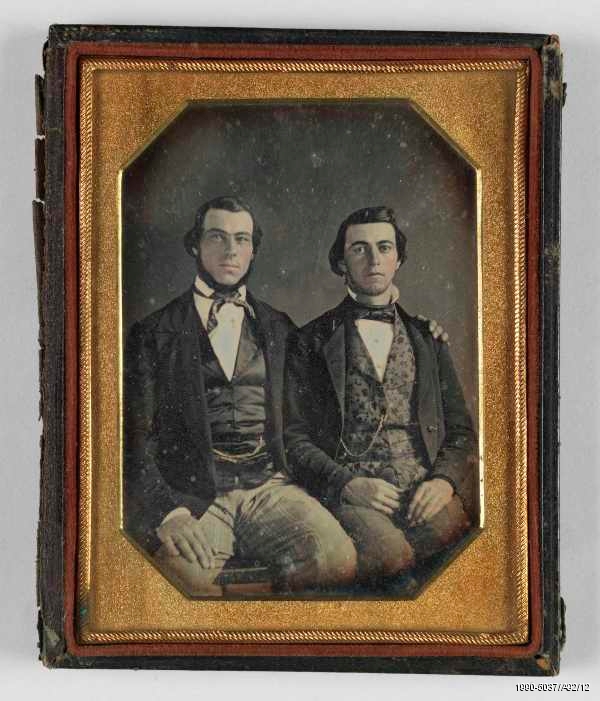

Only a few years after its initial announcement, however, exposure times had been brought down to a matter of minutes. This allowed it to be used for portraiture. Few could resist the opportunity to have a permanent keepsake of those they loved, and for an image on a metal plate it could be surprisingly affordable (figures I’ve come across suggest less than £11 for the most common size). Naturally, people would want to look their best, and so most daguerreotype photographs are ‘official’ portraits, where people would wear their finest clothes, and end up with a lovely cased image to show to their friends.

© Science Museum Group collection

© Science Museum Group collection

To me, this makes this image of the dog all the more endearing. During a time where people are just beginning to explore this novelty of photography someone has put forward the money to preserve their beloved pet for all eternity.

This image has featured on the museum’s Flickr page before, and the comments showed there was some confusion over whether the dog was alive or not at the time of the image being taken, due to the still rather long exposure times. However, as one commenter points out, the blurring effect around the head is a good sign that the dog moved slightly during the exposure, and so was likely alive at the time the photograph was taken. In fact, this effect can be seen in a number of images, especially those gathered by one Flickr user in this gallery.

So there you have it: the dog daguerreotype (or dog-erreotype, since we can’t resist a good pun).